Impact investments are investments made into companies, organizations, and funds with the goal of generating positive, measurable social or environmental outcomes alongside a financial return. The term “impact investing” is of relatively recent origin, only becoming popularized in 2007. The practice of investing for social—and not merely economic—return, of course, has a much longer history. This community wealth building strategy includes two key approaches:

- Socially Responsible Investments (SRIs) are investment strategies that individuals employ to generate financial returns while promoting social good. The most common form of socially responsible investment involves investment portfolios designed to exclude certain companies based on explicit social and/or environmental criteria. This is known as “negative screening.” However, positive screening, investment in companies that achieve some positive social benefit, is another SRI strategy.

- Mission-Related Investments are investment strategies that foundations and anchor institutions employ to generate financial returns while promoting mission-related goals. Program-related investments (PRIs) are one such strategy that has played a role in building wealth in low-income communities. Depositing money in community development financial institutions (CDFIs), such as community development credit unions or community loan funds, is another. In additions to PRIs and CDFIs, some foundations, such as the F.B. Heron Foundation, have taken a broader role to ensure that their entire corpus is aligned with the Foundation’s mission. Thus, in each asset class (such as stocks, bonds, loans, and private equity placement), Heron seeks to ensure that investment priorities align with the foundation’s social values.

Impact investments play a critical role in building community wealth for several key reasons. Because impact investments typically earn a positive, albeit frequently below-market economic rate of return, funds used to make them can be re-invested, and thus, help support ever greater social and economic change. Many impact investments support initiatives that have the potential to create new jobs, catalyze small business development, and boost home ownership. Additionally, since the majority of PRIs are directed towards housing, community development, and education initiatives, PRIs provide significant support to the community development corporation (CDC) and community development financial institution (CDFI) industries. Demonstrating the potential of these investments, the Living Cities program (which supported over 200 CDCs in 23 cities in the 1990s) used roughly $150 million in foundation PRIs and corporate support to leverage $750 million in community development investments. Finally, screened investment accounts can help steer assets to companies that support the communities in which they are based, protect and improve the environment, and provide workers with adequate wages and benefits.

Socially Responsible Investments

One feature of the U.S. economy is the growing importance of institutional investors, including pension funds, universities, and foundations. A September 2005 report by The Conference Board found that at the end of 2003, public sector pension funds alone had $2.27 trillion in assets, of which roughly $1.3 trillion were invested in stock. Public pension fund stock holdings totaled 9.7% of the stock market's value in 2003, up from 7.6% just three years before. Foundations also have large asset holdings, which now exceed $500 billion, with $323 billion invested in the stock market alone as of 2003. University endowments also have significant asset holdings. A 2011 report of National Association of College and University Business Officers found asset holdings of $408.1 billion among the 823 schools surveyed.

Increasingly, institutional investors and other socially-minded investors have used their clout to influence the behavior of large corporations. Dr. Carolyn Kay Brancato, Director of The Conference Board's Global Corporate Governance Research Center, notes that public pension funds “tend to be the most activist in demanding corporate governance reforms and will continue to have a profound impact on every company not only in the U.S. but also in global markets, since U.S. investors have tended to be out in front of global shareholder activism.”

Typically, socially responsible investing takes three different forms: screening, shareholder activism, and community investing. These different methods of social investing may be used separately or in combination with each other. While the community investing mechanism is most directly focused at building community wealth, all forms of socially responsible investing open up important possibilities for new funding streams for asset development.

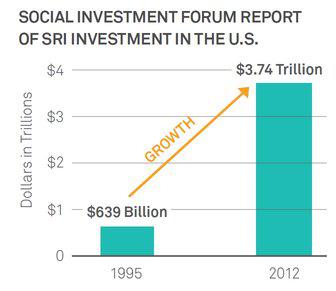

The most common form of socially responsible investment is the screened investment account. These include both socially screened mutual funds and socially screened separate accounts managed for individual and institutional clients. Screening can be positive, meaning that the fund or account has a preference to invest in socially responsible companies. Screening can also be negative: the 1980s movement to disinvest or "divest" from companies doing business in apartheid South Africa (and which contributed to that regime's demise) was one important factor that led to today's socially responsible investing movement. Other examples of negative screens include bans on investing in certain industries (such as tobacco or defense) and bans on investing in companies with poor labor or environmental records. According to the Social Investment Forum, the number of dollars invested in screened assets has climbed from $162 billion in 1995 to $2.98 trillion in 2007.

Shareholder activism involves using stock ownership as leverage to introduce shareholder resolutions and otherwise act to influence corporate behavior. Measuring such activity is difficult since often the most successful interventions are the ones that work "behind the scenes" to affect change. Nonetheless, there has been plenty of visible activity as well. Shareholder resolutions on social and environmental issues climbed from 299 proposals in 2003 to 348 in 2005, a 16 percent increase. By 2007 shareholder resolutions reached 367. Social resolutions reaching a vote rose more than 22 percent from 145 in 2003 to 177 in 2005. Institutional investors that sponsored or cosponsored resolutions on social or environmental issues controlled $739 billion in assets in 2007, a 69 percent rise over the $448 billion in assets counted in 2003. According to the 2010 Trends Report by the Social Investment Forum, this value is now estimated to be $858.8 billion.

The final form of socially responsible investing is community investing. This involves directly taking funds out of investments in multinational corporations and actively reinvesting them — through community development financial institutions or CDFIs — in local communities that face shortages of capital. Currently, the Social Investment Forum Foundation and Co-op America are leading a campaign to persuade social investment funds to dedicate one percent of their assets to support the growth of CDFIs. Assets in community investing institutions rose from $25 billion in 2007 to $41.7 billion at the start of 2010.

History

Many early promoters of impact investing were religiously motivated. For example, John Wesley, one of the founders of Methodism, preached in the late 1790s that people should avoid companies manufacturing products that could sicken workers. The use of PRIs has actually been traced back even further—in the 18th century, Benjamin Franklin, considered America’s first social investor, used instruments such as revolving loan funds to support a range of charitable organizations. The Ford Foundation, which began its PRI program in 1968, is credited with catalyzing the use of PRIs in the foundation field.Program Related Investments

Program-related investments, also known as PRIs, leverage limited foundation dollars—most often by providing long-term, low-interest loans—to promote community wealth building and other mission-related foundation goals. The Ford Foundation, one of the first to use PRIs, began its program in 1968. According to a 1974 review of its first five years, even after accounting for loan losses, administrative costs, and the opportunity cost inherent in providing money at a below-market rate of interest, Ford found that “$1 million invested in a PRI is the equivalent of $5 million in grant expenditures.” Since then, the use of PRIs has grown steadily. In 2006-2007, the top five PRI providers were the ALSAM Foundation, followed by the Ford Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the David & Lucile Packard Foundation, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

A survey conducted by The Foundation Center found that foundations provided a total of over $387.6 million in program-related investments in 2007. Although modest (the amount was slightly under 1% of the amount of grants disbursed), these PRIs leverage over $1 billion a year, a considerable sum.

Their importance is even greater than their numbers, as PRIs are a leading practical example of a growing trend of "double bottom-line" investing (i.e., investing that seeks a blended financial and social return). According to a 2002 study conducted on behalf of the Rockefeller Foundation, as much of 75% of actual “double bottom-line” investing in the United States can be said to take the form of PRIs.

At present, most foundations allocate just over the legally mandated 5% minimum of assets to mission-related activity. Many are now calling on foundations to place some of the 95% of their remaining assets in "double bottom-line" investing. The Heron Foundation has been a leader in this area, investing 20% of its assets in grants, PRIs, and other forms of social investment as of July 2005.

The effects of PRIs on community wealth building have been substantial, helping support the growth to scale of community development corporations (CDCs) and community development financial institutions (CDFIs). The long-term, low-interest financing that PRIs provide has enabled CDCs and CDFIs to leverage significantly greater private funding. To take one prominent example, the Living Cities program (which has supported over 200 CDCs in 23 cities over the past decade) used roughly $150 million in foundation PRIs and corporate support in the early 1990s to leverage $750 million in community development investment.