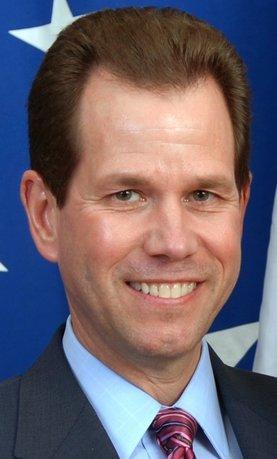

Interview of Paul Hazen

Executive Director, U.S. Overseas Cooperative Development Council (Washington, DC)

Interviewed by Steve Dubb, Research Director, The Democracy Collaborative

January 2012

Paul W. Hazen is the Executive Director of the U.S. Overseas Cooperative Development Council (OCDC). Previously, he served as President and Chief Executive Officer of the National Cooperative Business Association (NCBA), the leading national cooperative membership association in the United States. In the fall of 2011, Hazen announced that he would be stepping down as CEO, after serving as the organization’s leader for 13 years and as a member of NCBA’s staff for nearly 25 years. As CEO, Hazen led several important NCBA initiatives, including the creation of the “dot-coop” Internet domain name for cooperatives. Also, under Hazen’s direction, NCBA’s international cooperative development program has grown to more than $32 million in annual funding, with 30 projects in 18 countries. Hazen serves as a board member of the Consumer Federation of America, and the International Cooperative Alliance.

Could you explain how you came to be involved with cooperatives and what inspired you to focus so much of your life’s work on that sector?

I became involved with co-ops in a formal way when in 1984 I became the executive director of Rural Housing, Inc. in Wisconsin. That is a nonprofit organization that was founded by the electric co-ops to promote and build cooperative housing in rural areas of the state. Prior to that, growing up in Wisconsin, I had been exposed to many cooperatives. My parents were members of the electric co-op. And many agricultural co-ops held their annual meetings as public events – with picnics that brought together the whole community. So even though my parents weren’t farmers, I also attended those.

I first became really interested in working for co-ops, though, when I worked in the 1970s for Representative Al Baldus. He was on the House Agriculture Committee and Chair of the Dairy Subcommittee, so I would go to many co-op meetings with him. Really, co-ops were his political base. Attending these meetings, for the first time, I began to understand these were economic businesses that were striving for the success for their members, but that they also had a social purpose. It was so logical and made so much perfect sense. From then on, I knew I wanted to get involved with co-ops. Later on, I was able to do just that — first, with the housing cooperatives and then in 1987 when I became director of consumer cooperatives at NCBA.

You hail from Wisconsin, where co-ops play a significantly larger role in the overall economy than they do nationally. Could you discuss how your experiences in Wisconsin have informed the way you look at the role of cooperatives nationally?

There is a very strong cooperative movement in Wisconsin. The greatest lesson I can take away from that, I think, is that the cooperative movement was able to build an infrastructure that supports existing co-ops and makes it easier to form new cooperatives.

Part of this was a strong extension service through the Department of Agriculture. There was also a lot of cross-sector work ensuring that there were good laws. Because there was a critical mass, the environment there is so correct for the development of cooperatives that it has become a model for the rest of the country. That level of infrastructure does occur in some other places, but certainly the Upper Midwest has developed a co-op environment and culture to the extent that there is a continuous growing co-op movement in those upper Midwest states.

When you first came to work for NCBA in 1987, NCBA was already a mature organization with 71 years of history behind it, but surely the past two-dozen years have brought considerable changes. Could you discuss how NCBA has changed over this period and also what has stayed constant?

What has stayed constant is a commitment to the coopeative principles and values. We always keep those out and front. We see ourselves as the protectors of those principles and values. While they need to evolve and be flexible, those basic fundamentals stay in place. A commitment to cooperative development, both domestically and internationally, that has been constant. I think one thing that we have added is a commitment to being a common table that brings all of the cooperatives together. That has changed. We have had a real focus on making sure that all co-op sectors are involved. Back in 1987, purchasing, worker, and daycare co-ops were not at the table.

A real concerted effort was made to make sure that everyone has the opportunity to participate. That’s a real positive change. Another change is that in the 1980s we had perhaps one woman on the board of directors. Now at some points we’ve had up to 40 percent of the directors be women. So that’s a real positive change. The global view that we have a responsibility to participate with cooperatives in the world, not only in our development work, but engaging with our colleagues, that has also been a constant.

Could you talk also a bit about how the nature of the co-op movement in the United States has shifted over the past couple of decades? What sectors or market segments are seeing a growing co-op presence? Are there any sectors that have been declining?

As an overall issue, I am seeing much more focus on cooperative identity in various sectors. In the electrical cooperative sector, they have done a tremendous job. The credit union movement is coming up behind that. Of course we see that strong sense of co-op identity with worker and food co-ops. Overall, there has been a generally positive shift, with more cooperatives and larger cooperatives embracing their co-op identity.

Where we are seeing real development occurring is with worker and food co-ops. The recent recession is a big driver, but also people’s attitudes are changing. People are asking what is the role of business in community. People are expressing a desire to have a greater say in that. We are continuing to see fewer credit unions but more memberships. In order to compete, credit unions have to get larger and one way they are doing that is with mergers. But there has been a great spike in growth in the past 1-2 years in response to the financial collapse and the ongoing shift of the concentration of wealth in fewer people. Credit union expansion is a natural response to that.

We do see fewer farmer co-ops because we have fewer farmers. So there are fewer cooperatives, but the percentage of the market that cooperatives are engaged in continues to grow. One area that is going to be really tough is with telephone cooperatives. It is a very competitive marketplace and the technologies make it difficult to compete. That is an area where we are not seeing growth. We are seeing growth with electrical co-ops where suburbs expand into what were formally rural areas, bringing new members. Purchasing co-ops – independent businesses compete in a global marketplace – there too we are seeing continuing growth.

In recent years, NCBA has placed a greater emphasis on generating research regarding the economic impact of cooperatives. Can you discuss some of the findings of this research work to date and what you see as research priorities for the field going forward?

In the United States, there has been a tremendous amount of research on cooperatives in particular sectors, such as agriculture or finance. But there has been little comprehensive research about the sector in general and little hard research about the competitive advantages of cooperatives. So NCBA a number of years ago initiated a program to get that basic data. We are looking for data regarding such matters as the number of members, number of cooperatives, economic turnover, job creation – in the hope that academics would take that basic data on the impact co-ops have and apply that data not only nationally but regionally. And then drive deeper into the secondary benefits – does a cooperative provide competition to other businesses and drive down prices for people who are not even members? Is there a further economic benefit? That’s the kind of hard data and research we would like to have. Similarly with the tremendous amount of training and education for members – are they better citizens? Do they vote in a higher proportion? Are institutions with cooperatively trained leaders more effective? We see this anecdotally, but we would hope to demonstrate that. That’s the real goal. We’re part way there. We need research in that area – over a period of time, rather than just a snapshot – to demonstrate the real benefits off co-ops.

Since a large part of NCBA’s work concerns international co-op development, could you explain some of the challenges in the international co-op development process and how NCBA has been able to meet those challenges over the course of the past decades?

NCBA was the first U.S. cooperative organization to do international development work. A real legacy is that we have gotten many other cooperative organizations engaged in that work, such as Land O’Lakes and Co-op Resources International. We also helped start the World Council of Credit Unions and ACDI-VOCA (Agricultural Cooperative Development International and Volunteers in Overseas Cooperative Assistance).

The impact that we collectively have around the world is significant. On the International Cooperative Alliance (ICA) board, I’ve come to appreciate that here in the United States we really do have the greatest capacity to do this cooperative development work in developing countries. We have a good funding source from the federal government and our members, but also the intellectual and human capacity to work in very difficult situations. We have helped develop over decades some very substantial cooperatives serving hundreds of millions of people – raising people out of poverty. Often the co-ops we develop provide people with their very first opportunity to have a say in their lives when they can vote for the board of directors. The challenges we face are that these days many donors and organizations don’t want to fund coop development. Well, that’s a bit strong – let’s just say that it is not their priority. They are looking to achieve such goals as wealth creation, democracy building, and the empowerment of women. We do all of those things through developing co-ops. But we need to change the dialogue. We need to say that co-ops are about those things. We need to ask how do we get those goals completed by developing and expanding cooperatives? If we can turn the debate around, then we can get policymakers and donors to think of co-ops as the first option of how to change people’s lives for the better.

What lessons do you see that NCBA has learned from its international cooperative development work that might be applicable in the U.S. economic context?

The approach that we take is a very bottom-up approach. Starting at the local level, we help people address their own problems. In the United States, we have had too much of a top-down mindset where folks come in and say, there is a need over here. And a bunch of professionals will get together and try to recruit members.

Bringing people together in the community and asking them what are the problems they want to address. Empowering them. We need to be much more attuned to that. We have an attitude in the United States that very low-income people don’t have the capacity to run cooperatives. That’s not our experience. Many of the people we are working with in Africa don’t have writing and reading skills, so we teach them literacy and numeracy skills. It is our belief that everybody has capacity to do this if they have the right tools.

One area that has always been a challenge for co-ops has been the issue of scale. Scale can boost organizational capacity, but can also mean larger organizations that may become disconnected from the communities they serve. Of course, NCBA itself is made up of a large number of cooperatives — some large, some small. Could you discuss some ways that NCBA member cooperatives seek to negotiate this balance?

Those co-ops that have a very strong Board of Directors can install into their cooperatives the culture that it is their responsibility to be the interface between the members and management. Where we find a disconnect is when management has too much say and doesn’t see the involvement and empowerment of the members as part of its business operations. A key question with any co-op, large or small, is whether the Board of Directors is creating opportunities for member engagement.

Health Partners, a Twin Cities-area consumer health care cooperative, has over 500,000 members. But they work at engaging their members. They do so by having open board meetings and they also do it by engaging with local councils. They really have a governance plan to drive down to ensure that the members are engaged. To me, that is the key: Have a governance structure where you don’t have a disconnect between the large co-op and the membership.

What is the level of presence of cooperatives in the green economy? To what extent is the green economy a focus of NCBA’s current work?

We can hope that we can step back and say in a couple of decades that we really own the green economy. We as a co-op movement missed an opportunity with fair trade. Almost all fair trade products are from co-ops, but we are not seen as part of the fair trade movement. The co-op movement is integral to the success of the green economy. Whether worker or consumer owned – there is a role for both. This should be our top priority. We have promoted green co-ops for a number of years. I don’t think we have done the job we could have, but the green economy is tailor-made for our domestic development initiatives and policy initiatives.

Thinking nationally, co-ops are enjoying new visibility in the United States, in part due to growing frustration with what might be called “American business as usual.” This new interest can be seen in many venues – among policymakers in Washington and the protestors of the Occupy movement, to name just two. What do you see as steps that the co-op movement needs to take nationally to build on this new visibility?

A common theme here is to ensure that there is the infrastructure and tools in place so that when people want to organize themselves into a user-owned business, they can accomplish that. Make sure there are good laws, educational materials, and technical assistance. This time we have a better chance of seizing on the renewed interest in co-ops. We do have a network of cooperative development centers. We have the financial institutions that help. And for worker co-ops, while we don’t have a lot of resources, we have many more than we had a couple of decades ago. It is the infrastructure that is the key and we just have to keep building upon that.

What are the co-op movement’s primary goals in the areas of legislation and infrastructure?

From a public policy standpoint, the action is going to be primarily at the municipal and state level, where co-ops can serve as incubators to fulfill the desire that there needs to be a different way to organize businesses that provide services to community. That’s better done at the municipal and state level. What the federal government can do is provide regulations and resources that make it easier for states and local municipalities to empower people. That’s going to mean money and that’s going to be difficult in the current economic situation. But if we are looking at jobs and economic development, we have results that we can demonstrate that co-ops bring long-term community and economic benefits.

Many within the co-op movement strive to be apolitical, while others see co-ops as a means to not only deliver business value for member-owners, but also as a mechanism to achieve a more just economy. What is your view of the relationship of cooperatives to such broader social economic justice goals?

One of the foundations is our businesses aim to create communities where there is social and economic justice. I recently was at the People’s Food Co-op in La Crosse, Wisconsin. Their mission statement is to create a cooperative economy in their region of Wisconsin. That was the vision of the people who started co-ops, both in urban and rural areas – to have opportunity, fairness, and businesses that provide competition and choice. At times we may have lost our way around that, but that’s what differentiates our businesses from pure investor-owner business—we have that double- and triple-bottom line in mind.

That can take many different forms. It doesn’t have to be one size fits all. I see that sense of vision in the credit union movement. It’s not just about getting people good financial services, but financial literacy – making sure their money works for them – and that members have access to all of the services they need and deserve.

The United Nations has declared 2012 to be the International Year of the Cooperative, an effort that, of course, NCBA helped promote. What do you see as the importance of these international developments for the co-op movement in the United States?

The greatest importance is that we have recognition from a global body of the cooperative business model. The United Nations has created a tagline – “cooperative enterprises build a better world.” Can you imagine if they said, “capitalist businesses build a better world?” They would be laughed out of New York City.

This is significant. So to be included as a part of that — it is very positive. Many around the world look to the model of U.S. cooperatives and say that is the model we need. That’s an important thing for U.S. cooperatives.

We’ve already seen the benefit from a public policy standpoint. From the Congress and federal government – there is already a higher recognition. I think we can expect a broader profile with policymakers around the country. Hopefully that will spur many more units of government to promote co-ops in their particular areas.

Seven years ago, the United Nations declared 2005 to be the International Year of Microcredit, a designation that helped spur an enormous expansion of that field. What can co-ops learn from this effort? What activities is NCBA doing in 2012 to take advantage of that opportunity?

The international year of microcredit really did catapult that in many people’s eyes as an economic development model that can produce real results. The lessons learned there are multiple. One is that in order for that to be successful, there needs to be a good environment – whether it is microcredit development or cooperative development. We look back now and many people thought that the microcredit movement could do more than they had the capacity to do. It is not because it wasn’t a good idea, but there wasn’t the capacity.

We have to be honest too – there need to be sufficient resources to have a maximum impact. If the appropriate resources are put into place, then we can achieve more—that is something we can learn from.

We are spearheading an effort to have an event with the President and cabinet secretaries to use 2012 to get that message across. We are pursuing an event at the White House and with other people in the administration. We would do that regardless of which party is in the White House. Social media is going to be our greatest vehicle to spread our message. We’ve been leading an effort for a global social media strategy. Working with all types of media. The microcredit movement did a very effective job of getting their message out with media – telling the stories. That is why the International Cooperative Alliance is having a story a day about the impact of cooperatives – that can be found at http://www.stories.coop. Each day a different co-op will be featured. At the national level, we work to interface globally and provide the tools that regional and local cooperatives can use to celebrate in their own communities.

The greatest legacy I think that we will have here in the United States is cooperation among cooperatives. The International Year of Cooperatives has given a reason for cooperatives to come together. In the past they haven’t had a reason, but now they do. We will see cooperation among cooperatives go on after the international year and that will be one of the most positive developments, I believe.

In many other countries, such as Canada or Italy, co-ops are seen as a central part of “social enterprise” and are studied as such in business school. By contrast, in the United States, cooperatives are largely seen as completely separate from “social entrepreneurship” and are rarely covered in business school. What steps do you think can either NCBA or coop movement activists take to help change this situation?

I think first we have to realize that we are part of the social enterprise community. I think folks sometimes believe we are outside of that. Our work to create a national cooperative investment fund shows that we just aren’t part of the social investing class or impact investing and we should be. We have to be much more deliberative about engaging with those other movements. We need to recognize it ourselves. That’s the first thing. And then we need to build relationships with those sectors of the economy.

And then we can use that to leverage with business thought leaders and academics, so that we become part of a broader social economy striving to common goals and use our resources to leverage these relationships. One of the things we are doing with the international year is a business plan competition to develop cooperatives. We hope that will raise the profile of cooperatives at some business schools around the country.

What do you see as the main priorities of the U.S. co-op movement going forward?

One priority is to be willing to cooperate with other cooperatives and put resources into cooperative development. Members of existing co-ops have many needs beyond those provided with existing co-ops. There needs to be much more emphasis on cooperative development and cooperation among cooperatives. More focus on cooperative identity and building that identity with the American public. Those are two or three of the most important things. Also, co-ops should not be afraid to use that identify to show that we are different and a better

business model for social and economic progress.

If you had to choose three accomplishments of NCBA’s work to date that you are most proud of, what would they be?

Our continued focus on the principles and values and co-op development, both domestically and internationally. I have worked hard to maintain our focus on that and our leadership in those particular areas. The inclusiveness of the organization in keeping all the sectors engaged and participating in the organization is key. It would have been easy to focus on those sectors that have more resources than others, but we want to make sure that everyone is around the table.

And what I have enjoyed doing is raising NCBA’s and U.S. cooperatives’ profile on the international front, mainly in the International Cooperative Alliance, but also in many other ways by demonstrating our commitment to a global co-op movement. The NCBA board and membership have supported me in that. And I really appreciate that.

For more information, please see the website of the National Cooperative Business Association at: http://www.ncba.coop.