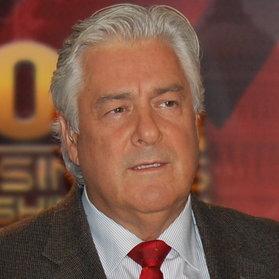

Interview of John Taylor,

President and CEO of National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC)

Interviewed by Steve Dubb, Research Director, The Democracy Collaborative

August 2010

John Taylor is the founding president and CEO of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC), which he has led since 1991. Today, NCRC brings together 600 national, regional, and local organizations from across the country that work together to increase the flow of private capital into traditionally underserved communities. A key focus of NCRC’s work has been to strengthen and enforce the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA). Passed by Congress in 1977 to end “red-lining” (a practice in which banks would draw a red line around low-income and minority neighborhoods and subsequently refuse to make loans in those areas), CRA creates an “affirmative obligation” for banks to lend money and invest capital in a safe manner in moderate and low-income communities.

Could you explain how you came to be involved with community reinvestment and what inspired you to focus on that sector?

I grew up in the public housing projects in Boston. My father was a union organizer and frequently unemployed because of it, so we always had a sense of responsibility to our fellow man. My father was strong about that. I was one of six kids, and the first one in our family to go to college. When I got out of college, I went to law school at Northeastern University and decided to focus my career less on the law and more on helping to end poverty in America.

I spent the first half of my career working on community development activities and running social service programs in the Boston area, including food banks and mediation projects. There was really an emerging community development movement in Boston at that time. When I worked on housing development, I began to see that some banks would regularly work with us and others would never even meet with us. So occasionally I’d fire off a letter to bank regulators, not giving much thought or hope that the letters would make a difference. But I ended up getting in this major battle in 1985 with the biggest bank in the city of Somerville. Long story short, after meeting with the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston and raising concerns, I procured a $20 million lending and investment commitment from that bank. At the time, in the mid-1980s, it was the single largest commitment in the country by a bank to an individual community group. This experience taught me about the power and promise that CRA held for low-wealth neighborhoods.

Next, a group of us, led by the Massachusetts Association of Community Development Corporations, which I chaired, and the Massachusetts Affordable Housing Alliance, focused our efforts on challenging the eight largest Boston banks to do more Community Reinvestment Actrelated lending. That effort let to an astounding (at least at that time) $1 billion commitment. The money funded a number of community programs; it also got me noticed in Washington, where Congressman Joe Kennedy and 16 national groups were in the process of forming the National Community Reinvestment Coalition. These included the National Low Income Housing Coalition, Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC), the Association of Community Organizers for Reform Now (ACORN) the Center for Community Change (CCC), the National Congress for Community Economic Development, the McCauley Institute, the Enterprise Foundation, the NAACP, and other groups. He called those groups together and said, “Look, you’re going to lose CRA if nothing is done.” In particular, he was worried that some of the Democrats in Congress were willing to trade it away.

The effectiveness of CRA at that point was due almost solely to efforts by Gail Cincotta at National People’s Action, but the organization’s geographic footprint was too limited to influence the government and ensure that banks across the country adhered to CRA’s requirements. What I did in Boston brought me into Washington circles, and eventually they hired me as the first staff person for the National Community Reinvestment Coalition. The Center for Community Change gave me office space to begin organizing the coalition. Because of my community development background, I knew a lot of groups that were doing affordable housing development, most of whom had limited or no involvement with CRA. I got their attention and showed them why CRA was important. Within a year we expanded the coalition from 16 groups to 100.

Our first order of business was to preserve CRA, because it really was under attack. We got together the 16 initial groups and several dozen others, and we managed to stop the Democrats (with the blessing of nearly all Republicans) from trading it away. That effort brought us together.

So we had won a victory and the next question was how to make CRA more relevant. Most people in neighborhood revitalization and community development had a very narrow view of CRA, or no view whatsoever. So we started by working to improve the quality of HMDA (Home Mortgage Disclosure Act) data that comes out of every transaction. We’ve always said that data drives our movement: the more you can point to what lenders are doing or not doing in underserved neighborhoods and compare that to what they are doing in wealthier neighborhoods, the more leverage you have.

The Community Reinvestment Act is very simple. It is only one-and-a-half pages long. But it doesn’t mince words. A bank doesn’t just have an obligation, it has an affirmative obligation to meet the credit needs of communities. That means the bank must actively pursue opportunities to investment in those neighborhoods. And, just in case there was any doubt, Congress added the words “including low and moderate-income neighborhoods.” It was a great law on paper, but it wasn’t being enforced. Our idea was to get more information into the hands of community groups so they could really use the law, and to ratchet up its enforcement.

I saw this in Somerville. If you were a working class truck driver and you tried to get a lender to give you a mortgage for a “triple-decker” home—and there are many of these three level row homes in Boston—the bank would say no, you couldn’t afford it. But if you were a doctor from Boston and you said “I want to buy properties in these neighborhoods and convert them into luxury condos,” they would give you a loan. So there was a financial access gap along income and class lines. And the banks were actively participating in gentrification. I saw that early on.

How has NCRC’s work evolved over time?

After stopping CRA from being gutted, we got HMDA information changed. I remember meeting frequently with Alan Greenspan during the 1990s and insisting that since Congress had mandated that home mortgage data be made available, the Federal Reserve needed to make it available in a more user-friendly form. You shouldn’t have to be at a university to be able to use that information, I argued. Because of our work, today, for a few hundred dollars, you can buy two CD ROMs that include data on every single mortgage listing the race, income, gender, geographic distribution, and census tract data on loans made that year. That really opened up a plethora of opportunities and empowered community groups across the country.

Then we had another victory. Following on the heels of that effort, President George H.W. Bush’s Justice Department brought the very first fair lending case against a bank that included a violation of CRA as part of the complaint. To this day, it bewilders me that this happened under Bush, but it did, and it happened in Atlanta. They filed in the morning and the bank settled in the afternoon. It was a shot heard around the financial services world.

We built on that example to show the need for strong enforcement of CRA. We were very critical of the regulatory agencies. The law says “an affirmative obligation,” not just a responsibility, to serve low-income communities. And yet pawnshops were opening in low-income neighborhoods while banks were closing. How was this possible?

In 1992, Bill Clinton was elected president. He announced plans to rewrite the enforcement of CRA and to create the Community Development Financial Institutions Fund on the same day. That day, the NCRC Board Chairman, Irv Henderson, spoke on the south lawn of the White House along with President Clinton and Vice President Gore, calling for CRA reform and a new CDFI fund. The Federal Reserve responded by saying they would send out a request to the field for comment regarding bank regulation under CRA.

This became the next great battle for our newly formed coalition. For the first time in the history of the Federal Reserve, people from the community out-commented the financial industry. After the new CRA reforms were announced, the Fed began their next meeting by recognizing the work that NCRC did in making sure the rules were reflective of community concerns. We had actually provided twice as many comments about what the CRA rules should look like as the banks.

One of the key reforms announced at that time was a change to CRA examination rules, which shifted the process for evaluating banks under the law. We transitioned from what was an almost exclusively process-oriented exam to one that based the banks’ CRA grade on their performance. So in the past, a bank simply had to have a CRA file somewhere—literally a folder entitled “CRA”—and they needed to have signs in the bank lobby noting that they adhered to fair lending laws. Nothing more. Because of the reforms at that time, we moved from that ineffective system to a results-oriented evaluation that required each bank to pass three tests measuring its levels of lending, servicing, and investments in low-income communities. As a result of this new system of grading banks, the universe began to shift for community development corporations and CDFIs, and for low and moderate-income communities.

Many CDCs and CDFIs don’t even know this history. Their ability to get support from these institutions is directly related to the work NCRC did to improve CRA’s effectiveness in the 1990s.

At that point, NCRC had 400 members. Today it is closer to 550 or 600. Over time, you could see an uptick in the amount of business being done by financial institutions in low-income areas. Not only did President Clinton change the rules, he also brought in someone devoted to CRA to head the Office of Comptroller and Currency (OCC). Finally, in Eugene Ludwig we had someone as head of the national banking system who actually cared and spoke about CRA. That was important. In the first year under Clinton, 10 percent of banks failed their CRA exam, which was unheard of.

But the banks responded. 120 banks changed their charters to be regulated by the OCC to be regulated by the Federal Reserve, because banks can choose how they are structured and who regulates them. Well, grade inflation was alive and well at the Federal Reserve, and today 98 percent of all banks pass their CRA exams. This happened at a time when banks were abandoning low-income neighborhoods, closing branches and leaving town.

Since then, and especially under President George W. Bush, there has been regulatory malaise. Banks simply have to be in existence and they’re already three-quarters of the way to a satisfactory grade. In effect, there were incentives to leave the banks alone. Some of Bush’s appointees, like Don Powell and James Gilleran, were outright opposed to CRA. Gilleran, who ran the Office of Thrift Supervision (OTS), actually said at an NCRC conference that he wasn’t “a fan of CRA, but since I am in charge of the OTS I guess I need to enforce it.”

It’s still a real problem: having a strong sheriff matters a great deal, and we haven’t seen one in recent years. We’re hopeful that we’ll get one to head the newly forming Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB).

We’ve done a lot of other things. NCRC played a key role in financial reform over the past year, working with Americans for Financial Reform to get the legislation passed. We tried to get CRA covered under the CFPB, but the banks’ lobbyists didn’t want a consumer protection agency with the authority to enforce CRA. They successfully removed coverage of CRA by the CFPB from the original bank reform proposal from President Obama.

What is the status of the community reinvestment movement in the United States today? In what ways have NCRC members been impacted by the Great Recession?

CRA is still an important tool in the effort to address poverty and financial injustice in low-wealth neighborhoods, one that could help ensure that pawnshops and check cashers aren’t serving as the banking services of choice. But like any law, it’s only as good as the sheriff enforcing it, and before the financial crisis, there was no real commitment on the part of the government to enforce the letter of the law. How could regulators give passing CRA grades to banks that had abandoned low-wealth neighborhoods where the only source of mortgage loans were subprime and high-cost mortgage lenders? All of this was allowed to happen. CRA took it on the chin.

A CRA agreement, which outlines a bank’s commitment to make loans and investments in underserved neighborhoods, comes out of negotiations between a bank and community groups; it documents the bank’s commitment to the community. Those written commitments added up to over $6 trillion through the present day! But when the sheriff was told to hold back, what we saw was the demise of the enforcement of those commitments. Regulators under Bush wouldn’t even consider those agreements when evaluating a bank’s CRA compliance. That’s absurd: nothing gives more insight into a bank’s activities and plans than their CRA agreement.

Bank branching—the opening and closing of branches—is another key component to low-income communities’ ability to access credit. But regulators under Bush would tell me that a branch is not a “credit need,” which the law examines, and therefore its presence in low-income neighborhoods was irrelevant to a bank’s CRA rating. Is access to a place to bank your money safely not a basic need of most people? We asked, “If banks don’t have vehicles like branches, how do they meet the credit needs?” Fortunately, today, the regulators have changed this practice. But banks are not rushing in to reopen their branches in low-wealth communities, at least not without some serious community organizing.

How does NCRC support itself financially?

Our revenue sources are very diverse. We receive support from foundations, member dues, and individuals. We have contracts with the Department of Housing and Urban Development and a number of state agencies to provide direct assistance to homebuyers and homeowners experiencing foreclosure. While we do not accept funding from banks and other corporations for operating support, some do help underwrite our national conference, which helps keep registration fees low for our attendees. This diverse portfolio has allowed NCRC to weather the storm currently faced by many organizations. In fact, NCRC has grown to 55 staff members, an all time high for the coalition.

As we have not relied upon banks for operating support, we have not been appreciably damaged by the decline in the banking industry. Support for our conference has gone down, but because we have a very diverse funding base, we’ve done reasonably well. We also own our own office building, called the National Center for Economic Justice, which generates some income. So we’ve managed to weather the storm in pretty good shape. Fortunately, foundations have generously recognized the importance of what we do.

It would appear that there has been some decline in community reinvestment due to the Great Recession. What do you see as the key problems that need to be addressed to restore community investment?

You’re right. There has been a decline. There is no greater way to reverse that than by strengthening CRA and ensuring that it is fully enforced. Not only was there lax enforcement during the George W. Bush years, but the administration also changed the frequency of exams. They created a small bank exam and a large bank exam, and kept inching up the criteria for a small bank, with the end result being that fewer banks had fewer exams. They also allowed banks to take subsidiaries, such as mortgage and finance companies, and let the banks decide whether or not to count the performance of those institutions on the bank’s CRA exam. That’s like allowing someone to decide their GPA without counting certain classes or grades. NCRC called attention to this, but the regulators ignored us. This all needs to be changed. Credit unions, insurance companies, and independent mortgage companies should have a CRA obligation. And to not have a public hearing when one large financial institution is buying another doesn’t make any sense.

Congress just passed a financial reform bill. It does make some headway in protecting citizens against bad loans. What it doesn’t do is create better access to credit for people, particularly those in low-income and minority communities. This is the unfinished business of the 111th Congress and [House Financial Services Chair] Barney Frank. I’m very confident that we will see Congressman Frank address this issue before this Congress expires. After all, what is the likelihood of CRA being expanded and strengthened if it doesn’t happen this year?

CRA is a fabulous law, but it was only very briefly under Gene Ludwig in the mid-‘90s that it really began to deliver on the promise that it offers, which is to make capitalism work for everyone. The uptick in sustainable lending in the 1990s was tremendous. This was all prime lending, all sustainable loans. These loans performed very well until the unregulated segments of the industry began to provide significant numbers of subprime, high-cost loans to low-income people.

The Federal Reserve has done a study that shows that less than six percent of subprime loans were made through CRA-regulated institutions. Had the independent mortgage companies been covered under CRA, they would have had their records dinged by the regulators.

Can you talk more specifically about the Community Reinvestment Modernization Act and how passage of the NCRC-sponsored legislation would impact communities?

The most significant thing is that it would expand the act to cover other segments of the financial services sector, such as credit unions, investment banks, independent mortgage companies and insurance companies. They would not all be treated the same, but they would all be covered, and it would ensure that credit-worthy customers have access to credit. This is the biggest complaint we hear from consumers today, that banks simply won’t lend. If we are to improve our economy and create more jobs, this has to change immediately.

If banks had not been allowed to close their branches, far fewer low-income people would have been driven to the subprime market. Indeed, we have found that every time we have successfully pressured banks to keep their branches open in low-income neighborhoods, they become viable. People think there are no resources to support banking in low-income communities. This is not true at all. Income is much denser in poor, urban neighborhoods: there may be he less average income, but the total income is greater. That’s what these banks have found, whether they’re in Watts in Los Angeles, Boston’s Roxbury, Chicago’s Southside, or Harlem: branches in these neighborhoods can be viable. There is nothing more important as an economic anchor than the presence of a bank in a community: it draws business into the area.

What impact has consolidation had on community lending? For example, the big four banks (Bank of America, Citi, JP Morgan Chase, and Wells Fargo) now hold 39 percent of all deposits.

Consolidation is important, but it is also important to note that we still have 9,000 other financial institutions. A lot of the big banks have assets that are never available to most communities anyway. Citibank, for example, which has a presence in 100 countries, may look like a huge bank, but a) not all of their assets are in America, and b) not all of their assets are in retail banking. But retail banking is still very important. The independent mortgage companies ate the lunch of the banks by selling bad lending products. They said, “Fine, if banks won’t lend in lowincome communities, we will.” And they made a huge number of subprime loans. It is important to note that this lending wasn’t about expanding homeownership; less than 10 percent of loans went to new homeowners. This whole debacle was actually about refinancing, buying a bigger house, or expanding the house.

Consolidation still needs to be dealt with. Competition is good and healthy, and I’d rather see more financial institutions than less. I don’t want to see our financial services sector evolve into a “drugstore world” where there is only CVS, Walgreen’s, and Wal-Mart. With consolidation, decisions are made centrally and banks become less connected to communities. And fewer quality jobs become available. So I say, the more the merrier.

We love the idea of having banks with boards of directors who actually live in the community; when you have a board made up of members who live three states over, you’re going to have more difficulties ensuring that local community needs are considered in the corporate boardroom.

That’s the key role of community reinvestment activism: to make sure the credit needs of communities without access are met: It’s not just an abstract matter of justice; it’s also the law. Even some people in community development don’t realize what a debt of gratitude so many owe to this kind of activism. Without it, not many community investments would have been made. The regulators went to sleep on this; they took a long nod. But they’re awake now. Lo and behold, they’re finally learning that banks and companies that do bad community loans really affect the safety and soundness of the system. Who knew? We did. We told them and they didn’t listen.

NCRC is a fairly rare organization in Washington in that it does a lot of policy work while maintaining a vibrant grassroots organization constituted by over 600 groups across the country. How do you manage the challenge?

It’s true; it is rare. The way you do it is you make a commitment to it. You have to respond to the power and interests of your grassroots members. We have a board of 26 men and women— all of who are community activists—and that’s the core source of our success, more than any person on our staff, including me. You also have to be in constant contact with the membership and never take their involvement with you for granted. I remember, as someone who spent years running local organizations, how busy and often short staffed we were, and how challenging it was. You have to be there for the leaders of local organizations.

The membership elects a third of the board of directors every year. This insures that our members have direct input into the paths the coalition takes. I work for that board and I never forget that.

We cover board members’ expenses to travel and participate in NCRC activities. This allows us to attract not only the well-heeled organizations, but also smaller groups. And we spend a lot of time every couple of years deciding key questions related to our mission and programs; every three years, we develop a new strategic plan, from soup to nuts. We constantly reexamine our mission: is it current, is it as relevant as it needs to be?

As a coalition, we are frequently called on to perform direct services, such as job development and foreclosure prevention. We’ve helped tens of thousands of people facing foreclosure to keep their homes. We’ve provided assistance to hundreds of minority and women-owned businesses, and trained 5,000 financial literacy experts.

NCRC performs numerous direct services because we recognize that doing it is necessary to fulfill our mission; it also informs our policy work. But we never allow ourselves to get too far from our core mission of advocacy and organizing, being the voice of the people, in order to make capitalism more democratic and ensure that the financial services sector works for underserved people.

What is the status of the Global Fair Banking initiative? Do you see specific lessons from abroad that might inform community investment practices in the United States?

The Global Fair Banking initiative is alive and well, in spite of never having been highly funded. We’ve received funding for it from the Ford Foundation in the past, but for the most part we piece together the budget. In spite of that, we have seen some remarkable successes. We’ve created a European counterpart, the European Committee for Responsible Credit (ECRC). They’re now celebrating their sixth year; I just went to Hamburg to speak at their conference.

It’s composed of NGOs (nongovernmental organizations) from 29 European countries that work on financial laws in Europe to keep out abusive subprime lending.

We have also created a Global Fair Banking website, thanks to the work of NCRC board member Maryellen Lewis. This allows us to remain in constant contact with NGOs from around the world to share ideas, strategies, laws, regulations, and other information relating to financial inclusion and the prevention of abusive lending.

We’ve also worked in Central America, South America, India, Australia, and South Africa. South Africa now has CRA and HMDA-like legislation. We’ve had a great deal of success in building this global communication about mechanisms that can increase wealth and investment in underserved areas. It is intriguing that the private sector in the United Sates has an affirmative obligation to be engaged in this; in most countries, affordable housing started out as a social enterprise, but they are heading towards a private sector model because the governments cannot afford to maintain it.

What I learned more than anything from our international work is that regulation matters and consumer protection matters. The consumer protections they have in many parts of Europe just don’t allow for predatory lending. They punish the lender severely. In one case I learned about, the courts forgave not only the penalties on a high-cost loan, but also the principal. They did this as a signal to show financial firms that it’s not permitted. It really matters when courts are allowed to protect consumers from abuse.

They are really interested in CRA over there. Several countries—France, Germany, and England—are seeking to pass CRA-like legislation. Just like us, they’re trying to create a more democratic capitalism. You can’t just lend money to the well heeled; there has to be a way for the system to invest in anyone who is credit-worthy.

Can you talk a little about NCRC’s effort to create regional organizer positions? How far along is the effort? What do you see as the challenges and successes to date?

We’ve filled six new organizer positions, all aimed at strengthening NCRC’s relationship with member organizations and other nonprofits. Currently, they’re all focused on ensuring that this congressional session doesn’t end before a real effort has been made to increase people’s access to credit, which means expanding and modernizing CRA. Eventually, our organizers will work more directly in the field in different regions. For the time being, they are being trained and immersed in NCRC’s diverse programs and projects as well as our mission and goals.

Could you discuss NCRC’s GROW (Generating Real Opportunities for Work) initiative? What is its current level of development?

The idea is that in seeking to stabilize and develop neighborhoods, you can’t just concentrate on the housing side of the sector; you have to create jobs. A lot of these neighborhoods will need to be rebuilt and there is a tremendous need for infrastructure, so why not train people from these neighborhoods so that they can be directly employed to regenerate their own communities? It’s a concept that’s getting attention within some government agencies, HUD in particular.

How does NCRC work with community organizing networks (such as the Center for Community Change)? How does it relate to community development financial institution (CDFI) networks, such as the Opportunity Finance Network or community development corporation (CDC) groups? What can be done to improve coordination?

One of the key reasons NCRC has been successful is because we have representatives from all of those groups as members of the organization. When we get together, whether on a listserv or at conference or regional setting, there is always a diversity of perspectives presented. It isn’t an either-or situation: we can always find common ground, mainly because as diverse as we are, we all want to ensure communities’ access to capital and credit. Certainly, you’ll have people in advocacy who don’t think community development is at the heart of the matter, or vice versa. Of course, both of them are wrong. Those who are seasoned realize that the most powerful community development and advocacy efforts bring in groups with connections to all of the elements that make up a neighborhood.

To revitalize neighborhoods, do you need CDCs? Absolutely. Do you need CDFIs? Absolutely. Do you need advocacy groups? Very much so. These organizations need to work together: that’s when we’re the most powerful and can affect the most change. For us, this attitude relates back to having a board of directors with a connection to underserved communities. We never get away from our core mission because my board wouldn’t stand for it. It is about really understanding that we are all foot soldiers in a very large battle. We need to work together, or we won’t win. We don’t need to spend a minute babbling about differences.

What are NCRC’s priorities within the green economy?

Fifteen years ago we were writing to regulators complaining that low-income neighborhoods were being targeted for the production, storage, or disposal of toxic products, and that banks were financing this. Now we are thinking more strategically. I think there is a real opportunity for environmental groups, community development organizations, and advocacy groups to work together strategically to develop both quality, clean, green jobs and housing. NCRC’s vision of a community is one that is diverse, healthy, and vibrant.

It is important for each to learn more about the other. Creating sustainable communities must involve green thinking and practices throughout the process of development. We need appropriate technology, greater efficiencies, and less toxicity. All of that relates to development—and developers and environmentalists are beginning to work together on both sides of that ledger. That’s certainly what we’re promoting.

Civil rights activists, faith-based groups, and community organizers need to understand why their different fields of interest (such as the environment, health care, or education) need to complement each other, and why we need to spend time integrating our area of expertise with others’. You can’t just build a nice house in a polluted zone with no health care. Our efforts have to evolve into a more holistic approach.

For those of us working on legislative issues, eventually all roads will lead to campaign finance reform. Until we fix that, not much can change. I actually ran once for Congress, so I learned firsthand the role that money plays in an election. If you can’t get on TV, if you can’t get on the radio, you can’t get heard. So millions of dollars are spent on elections, and that influences who winds up representing us. This country has a lot of very bright and dedicated people who really care about its future. But that isn’t the first criteria for getting elected; the first criteria is the ability to raise money. Anyone in the business of community reinvestment and neighborhood revitalization has to be engaged in making sure people get registered and vote, so that politicians are forced to see that they need to put people first and campaign financing and reelections second. We have the best Congress that money can buy—Senator Durbin said that in this session. And he’s absolutely right.

What are NCRC’s main priorities going forward?

Our main priority is CRA modernization and continuing to build a local grassroots movement that influences regulatory agencies and elected officials, so that our system of capitalism can be genuinely democratic. So people who pay their taxes have an equal opportunity to borrow money—as long as they can pay it back—as any one else. Within that, we have a lot of priorities related to job development and ending the foreclosure crisis.

We still have an ongoing foreclosure crisis? What solutions is NCRC advocating for?

Yes it’s still continuing. There are another 3-4 million homes that are on a path to foreclosure in the next year or so. We’ve been advocating for a more aggressive solution since the very beginning, first to Secretary Paulson and then to President Bush back in 2008. We proposed a program called the Homeowners Emergency Loan Program (or HELP Now). The program was a broad-scale loan purchase and modification program that would have bought loans at a discount and passed the discount along to the homeowner, making the loan affordable. Once the loan was performing, it could be refinanced or sold to the private market, with a guarantee, if necessary.

You cannot have a federal foreclosure program that relies on voluntary compliance by the industry. The government has to mandate participation in the modification, and they have to mandate principal reductions. At one time, it looked like the government would actually take up something like HELP Now—that is, buy loans at a discount and pass the discount on to the borrower. We know it’s possible, and profitable, because this is what Lew Ranieri, the inventor of the mortgage-backed security while at Salomon Brothers, is now doing with his own fund. He’s buying the loans at a substantial discount, making them sustainable for homeowners, and then getting FHA [Federal Housing Administration] to refinance and receiving double-digit returns for his investors. This is what the government should be doing.

Every few months the Obama administration comes up with something new. The government should be buying loans in bulk and modifying them to be good, sustainable loans. These bright guys in Washington keep coming up with one voluntary program after another, no matter how many months go by with data showing that it isn’t working.

If you had to choose three accomplishments that you are most proud of at NCRC, what would they be?

First, preventing CRA from being repealed. Second, changing the way that banks are examined under CRA. Third, building a grassroots movement focused on economic justice and financial inclusion that is an outgrowth of the civil rights movement. I’m most proud of the last part.

Is there anything else that you would like to add?

One further thing I should mention about my background is my education. I came from a family where my mother and father never went to college. I had three brothers—all went into military service—and two sisters. In high school, I was going to an all-boys public school in inner city Boston, which was 80 percent black. To put it politely, not a lot of educating was going on in that building. Then through the Catholic Church, a family from a well-to-do suburb invited me to live with them and finish my last two years of high school in this suburban community. The quality of education was such a complete contrast. Without a doubt, I wouldn’t have gone to university were it not for those last two years of high school. Most people in this country don’t know what it’s like to be poor in a community that has very little economic opportunity and not a lot of role models. Your options are limited; when I was young, they amounted to joining a union or the service, or you just didn’t think about it. Ensuring the success of the least privileged among us comes down to developing sustainable, healthy neighborhoods.

Capitalism appears to be one of the better economic systems that have been developed, but it still doesn’t work well for low-income neighborhoods. It needs to be more democratic, and there has to be fairness and ethics in the process. Clearly, in my view, CRA holds the main key in the effort to build wealth and revitalize poor neighborhoods. This is my mission and why I work for NCRC.

For more information, please see the website of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition at: http://www.ncrc.org.